#46: All in the Family

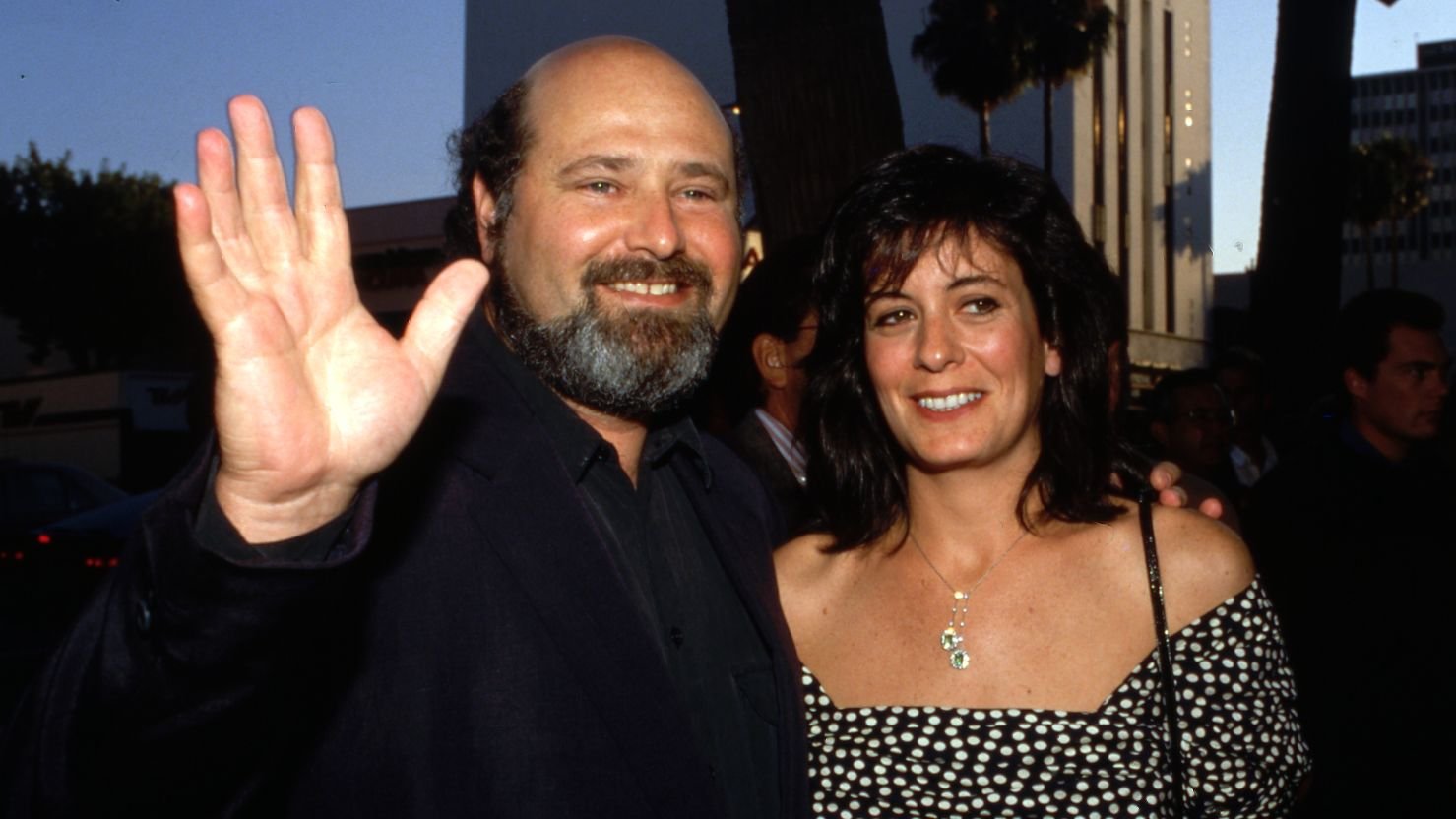

Rob & Michele Reiner, צ"ל

Let’s face a sad, sad fact: the last couple of weeks have been among the worst, most bloody and horrifying on record. I mean the murder of 11 Jewish men, women and children (ranging in age from a ten-year old to an 87-year-old retired mechanic and Holocaust survivor); the murder took place on the first night of Chanukkah on Australia’s Bondi Beach. Then there were the shooting deaths of two students at Brown University, followed two days later by the murder of an MIT professor (Portuguese plasma physicist Nuno F.G. Loureiro, the director of that prestigious university’s Plasma Science and Fusion Center); and just this past Sunday, December 14, 2025, the one that hit closest to home: the horrifically gruesome stabbing death of Director/writer/actor/activist/philanthropist/100% mensch Rob Reiner, and his wife/actor/partner/photographer/eternal soulmate Michele Singer Reiner, allegedly at the hands of their son Nick who has been arrested on two counts of first-degree murder, and is now being held without bail pending an arraignment scheduled for January 7, 2026.

What makes this last unspeakable act the worst . . . for some of us . . . is that it took place in one of the most tightly-knit communities on the face of the earth. It’s not that every actor, director, producer, choreographer, costumer or editor has a thriving friendship with everyone else in “the industry.” Rather, it is that we are born (at least for those of us who are natives) and live, work, are educated and play in, the most collaborative art in the history of the world. And despite whatever reputation “La La Land” (g-d how I despise the term!) may have, it has long been the most creative, least boring, and most unique place on the planet to spend at least part of a life. . .

When you get down to brass tacks, Hollywood (the real one in Southern CA, not the one in FL) is a pretty small place. Those of us who were born here (and there really haven’t been that many) pretty much know that it consists of less than 22.1 sq. miles, and is bounded on the North by Hollywood Boulevard from La Brea Avenue to Wattles Garden, and Franklin Avenue between Bonita and Western Avenue; on the South, the border is Melrose Avenue; on the East it’s Western Avenue; and on the West, it’s either La Brea Avenue or the West Hollywood city line. It’s never had a huge population; the neighborhood called “Hollywood,” which itself has just a tad over 3.5 sq. miles, has had a pretty steady population of just under 20,000 for decades. It is a place of few - if any - mansions; most people live in what are known as “bungalow colonies.” Back in the days I worked on Hollywood Boulevard at KFWB (“You give us 22 minutes, we’ll give you the world”) I inhabited one of these bungalows at 2420 3/4 (yes a fractionated address) Argyle Street, consisting of a small bedroom, a smaller living room/dining room, a miniscule kitchen and a ginormous closet . . . originally built back in the days when movie extras had to provide their own costumes. The real Hollywood is a tiny slice of a much bigger world universally known as “Tinseltown” . . . another name I have never been able to wrap my head around.

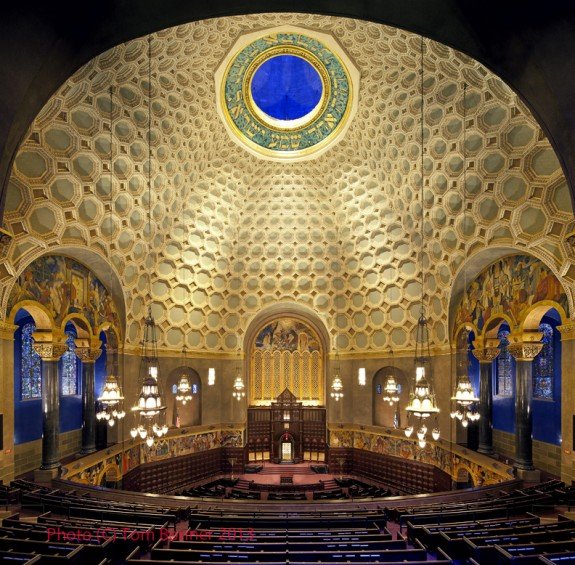

This Hollywood, where the actors, directors, writers, choreographers, agents, attorneys, and financial folks (along with their families ) live and work, goes by many names . . . some well known, some known only to the locals. These are places like Beverly Hills, Brentwood, Holmby Hills, Pacific Palisades, Marina Del Ray, Sherman Oaks, Woodland Hills, Encino and dozens of other pricey places. And yet, as vast and spread out as this “Hollywood” is, it’s still a pretty small town; people do know people . . . it’s almost as if the majority attend the same house of worship . . . let’s call it the “Our Lady of the Cinematic Arts.”

People in the arts, generally speaking, are a bit different from the rest of the human family. Most actors I have known, when away from the stage or footlights, are actually rather shy; putting on the face, the character and personality of a fictional being is the easy part; shedding that face, character or personality at the end of the day can be both difficult and painful. Acting, dancing, singing, directing and all the other various creative arts aren’t a walk in the park. Simply stated, it’s not a 24 hour-a-day hour party. It’s really, really hard work; up very early, spending a lot of time waiting, and then getting your beauty sleep. And once one job is complete, unless you are a superstar, it’s back to looking for your next gig. In many ways, the most important trait or skill in the performer’s bag of tricks is an ability: the ability to withstand rejection . . .

One of the most difficult, least forgiving aspects about “the industry” is that so many are public property. Imagine going to a restaurant, grocery store . . . even taking a walk in the park or along the beach . . . and being stared at by people who think they know everything about you. Being a script consultant, screenwriter, editor or makeup artist is one whole hell of a lot easier than being an actor; at least with the latter, one can live with a far greater degree of anonymity. Success is a two-edged sword: while it can earn one a pile of gelt, it can also drive you crazy.

Rob Reiner was one of the lucky ones; he was marked for success - both as a creative artist and as a human being - from an early age. The eldest of Carl and Estelle (Lebost) Reiner’s three children (sister Sylvia Ann is 3 years younger; the baby, Lucas, was born the year Rob became bar mitzvah), his parents were highly successful at just about everything they ever tried:

They were both happily and productively married for 65 years;

By the time Rob was 3 (1949), his father had already made his Broadway debut in the musical “Inside U.S.A.”, a hit that ran for nearly 400 performances.

By 1954, Carl, now associated with Sid Caesar and Imogene Cocoa on Your Show of Shows, was nominated for his first Emmy for Best Supporting Actor. He would eventually win 13 of them. Throughout a career as a writer, actor, director and producer, he would amass more awards than just about anyone in Hollywood history. Perhaps his greatest honor was being named recipient of the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor in 2020.

By the time of Rob’s birth, his mother, Estelle, had already been a successful jazz singer on radio for more than 5 years. Once the family moved out from Long Island, Estelle became a fixture at such venues as the Cinegrill (a restaurant/tap room long favored by Hollywood stars and writers), the Vine Street Bar and Grill, and Luna Park, a lush 400-seat supper club on S. La Brea. She also appeared in several films starring good friends Mel Brooks and Steve Martin.

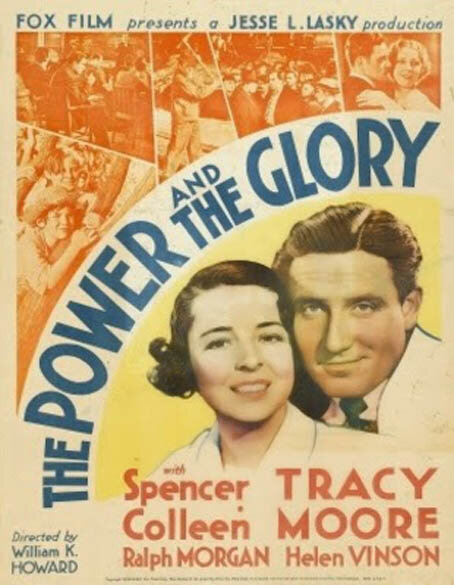

After a brief stint at UCLA, Rob got into the family business . . . first as an extra, then as a featured actor. In his 3rd small role, he played a character named Clark Baxter in the 1967 film “Enter Laughing,” written and directed by his father, and based on Carl’s own delightfully side-splitting 1958 novel about his own early showbusiness career. Over the next 4 years, Rob had both minor and featured roles in such popular TV shows as That Girl, Gomer Pyle: USMC, The Beverly Hillbillies, The Partridge Family, The Odd Couple, and The Rockford Files. It was in 1971 that Rob became a star in his own right, beginning a 7-year, 184 episode run playing Archie and Edith Bunker’s son-in-law Michael “Meathead” Stivic on All in the Family, a show that would, in many ways, change the course of television history.

During the run of All in the Family, Rob was married to Penny Marshall, the sister of actor and filmmaker Garry Marshall (1934-2016), the creator of Happy Days (1974-1984), Laverne and Shirley (1976-1983) and Mork and Mindy 1978-1982). Rob and Penny, would be married from 1971-1981); Rob legally adopted Penny’s daughter who, as Tracy Reiner would become best known for playing pitcher Betty Horn in the 1992 hit A League of Their Own, directed by her mother, and starring Tom Hanks and Geena Davis. From all accounts, Rob’s divorce from Penny was a crushing blow; he became jaded about love - both in real life and on screen. That would eventually change in a big, big way . . .

After concluding his long run on All in the Family and, with the encouragement of Archie Bunker (actor Carol O’Connor) Rob moved on to the even more difficult world of directing motion pictures. Almost immediately, he, showed off his comedic chops at the helm of the musical mockumentary This Is Spinal Tap (1984), which became an immediate classic. He quickly followed this up with the more dramatic The Sure Thing (1985) and The Princess Bride (1987). Within 3 years, the industry realized that Rob Reiner was one of the best directors in the business.

Rob and Michele: In the Beginning

In 1989, nearly a decade after his divorce, Rob, while directing Billy Crystal, Meg Ryan and Carrie Fisher on the set of When Harry Met Sally, was introduced to photographer Michele Singer by the film’s cinematographer, Barry Sonnenfeld, best known today for Photographing the 1997 classic Men in Black. Michele offered him a new perspective on both life and love; one which would help turn him around . . . and in the process turned a romantic comedy into a modern classic. Their first date did not bode well: Rob told Michele she really shouldn’t smoke; and turn, Michele told Rob “. . . You really shouldn’t be so f—-fat.” Despite this less than auspicious beginning, the relationship worked . . . as did the film. Although the movie concludes on a happy note, with Harry (Crystal) professing his love for Sally (Ryan) on New Year’s Eve, the first ending was much more cynical—reflecting the initial conversations between Reiner and the world-class screenwriter Nora Ephron. As originally construed, Harry and Sally did not get together. But Rob Reiner’s budding relationship with the cigarette-smoking Singer changed his mind. In a 2024 interview, Rob Reiner told Chris Wallace “When I met Michelle . . . I thought: OK, I see how this works.” With the growth of Rob and Michele’s relationship, so did that of Harry and Sally: at the end of the film, they got married.

(Ironically, it should be noted that back in 1989, Michele was best-known for having taken Donald Trump’s photo for the cover of his 1987 ghostwritten bestseller Trump: The Art of the Deal. Whether he had any recollection of this when he issued his heartless, inhuman comment of her murder just a few days ago is anyone’s guess . . . I for one could care less; to rephrase Gertrude Stein, ”A shmuck is a shmuck is a shmuck” ).

Over the next 36 years, Rob Reiner became the entire cinematic package: producer (32 films), director (30), writer (55) and actor (a career total of 221 films and television shows). Some of his films were expensive bombs (most notably 1994’s North); many became much beloved classics in a host of genres, including A Few Good Men [1992], The American President [`1995], The Bucket List [2007], The Magic of Belle Isle [2012], LBJ [2016], and his last - completed but yet unreleased - work, the hauntingly titled Spinal Tap at Stonehenge: The Final Finale.

One of Reiner’s films that will no doubt receive renewed interest is 2015’s Being Charlie. Based mainly on the life of Rob and Michele’s son Nick (from a screenplay which he cowrote), Being Charlie hauntingly tells the tale of Charlie Robinson (played by Nick Robinson), a would-be governor’s drug-addicted son and his heartbreaking trek down the long, rough road of rehab. This film won the SAMSHA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) Award for the best film of 2015.

(SAMSHA, a U.S. government agency attached to the Department of Health and Human Services [DHH] was set up to lead public health efforts to improve behavioral health, focusing on preventing substance abuse, treating mental illness and supporting recovery through grants, evidence-based practices, data collection and national helplines. The Trump Administration, in its effort to “cut wasteful government spending”, gutted the entire program in early 2025.)

According to PEOPLE, Nick attended rehab 17 times, starting at age 15, and experienced multiple stints of homelessness in Maine, New Jersey, and Texas. “That made me who I am now, having to deal with that stuff,” Nick told the magazine in 2016. “...Now, I’ve been home for a really long time, and I’ve sort of gotten acclimated back to being in Los Angeles and being around my family. But there was a lot of dark years there.” Today, Nick sits in a jail cell in downtown Los Angeles, awaiting trial for the murder of his parents.

At the time of their gruesome murders, it is estimated that Rob and Michele’s net worth was somewhere in excess of $200 million. What they did with their money . . . and far more importantly, their time . . . is the stuff immortality is made of. Long a liberal activist, he and Michele were founders of the American Foundation for Equal Rights, which initiated the court challenge against California Proposition 8, that barred same-sex marriage in the state.

As early as 1998, Reiner chaired the campaign to pass California Proposition 10, the California Children and Families Initiative, which created First 5 California, a program of early childhood development services funded by a tax on tobacco products. He served as the organization's first chairman from 1999 to 2006. His lobbying, particularly as an anti-smoking advocate, led to his likeness being used satirically in the South Park episode "Butt 0ut”, where he was depicted as a morbidly obese, hypocritical tyrant.

Reiner was mentioned as a possible candidate to run against California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2006, but declined for personal reasons. At the time, he was quoted as saying "I don't want to be an elected official, I want to get things done." He campaigned extensively for Democratic presidential nominee Al Gore in the 2000 presidential election, and he campaigned in Iowa for Democratic candidate Howard Dean ahead of the 2004 Iowa caucuses. He endorsed Hillary Clinton in the 2008 election, and in 2015 donated $10,000 to a political action committee supporting her 2016 presidential campaign. After the 2016 election, Reiner continued to campaign against Donald Trump, calling him racist, sexist, anti-gay, and antisemitic. Rob and Michele became very good and close friends with Barack and Michelle Obama; indeed, on the day they were murdered, the Obamas were supposed to be over at the Reiner’s home in Brentwood. In September 2025, Reiner gave an interview with CNN, where he spoke out against Trump and the Federal Communications Commission. He said it "may be the last time you ever see me", in reference to the suspension of Jimmy Kimmel Live.

Within the Hollywood community, Rob and Michele were known as an ideal couple; one that was always there with an open heart, and an open wallet. Rob was especially generous with his time and talent, and would often give breaks to actors, writers and other members of the Hollywood family down on their luck . . . regardless of their political leanings or beliefs.

One of the best-known such situations dealt with actor/director James Woods, a man of great talent who happens to have long been one of Hollywood’s staunchest political conservatives. Back in 1995, after portraying political bagman John Erlichman in the Oliver Stone hit Nixon, starring Anthony Hopkins as the nation’s disgraced 37th POTUS, Woods, career hit the absolute skids. As the old saying goes, he couldn’t get hired to sweep the set at the end of a day’s shooting. Then along came Rob Reiner, who hired Woods to play Brian De La Beckwith, the notorious white supremacist who murdered Civil Rights icon Medgar Evers. The film was Ghosts of Mississippi. Not only did the role revive Woods’ career in a big way; it earned him an Academy Award nomination for best supporting actor. Ever since, Woods - long one of Hollywood’s most steadfast political conservatives - has been a star both in front of - and behind - the camera. And he has never made any bones about the fact that he owes his revival and great success to Rob Reiner . . . a man he calls “a truly patriot.”

Speaking out on Donald Trump’s response to the murder of the Reiners - which Woods called “infuriating and distasteful,” he stated “I judge people by how they treat me, and Rob Reiner was a godsend in my life. We got along great; we loved each other … He was always on my side. When people would say to me, ‘Well, what do you think of his politics?’ I would say, ‘I think Rob Reiner is a great patriot . . . . Do I agree on many of his ideas on how that patriotism should be enacted, to celebrate the America that we both love? No. But he doesn’t agree with me either, but he also respects my patriotism. We had a different path to the same destination, which was a country we both love.”

This is not to say that there aren’t creeps, Cretans, and egomaniacal boors in Hollywood . . . just as there are in Miami, Boston, Tacoma and Excelsior Springs. Then too, there are nice, thoughtful, heimische (Yiddish for “unpretentious”) folks all over the place; it’s just that they don’t live in the spotlight’s blinding glare.

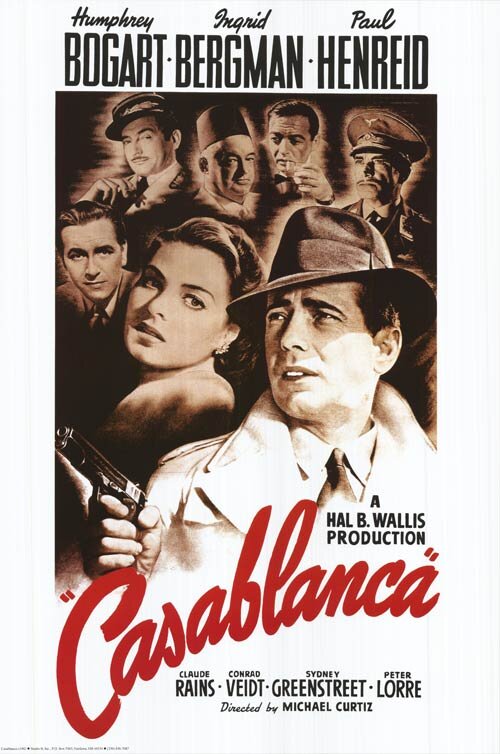

I for one am terribly grateful for having been born, raised and educated in one of planet earth’s greatest places. In oh so many ways, “Hollywood”, whether it be on Beechwood or Maple Drive, Addison Street, Glencoe or the 200 block of South Chadbourne Avenue in Brentwood (that’s the Reiner estate, which was built in 1936 by Henry Fonda, who then sold it in 1944 to Paul Henreid [Victor Laszlo in Casablanca] who then in turn sold it to All in the Family Producer Norman Lear, before finally being purchased by Rob and Michele shortly after their marriage) it’s a family, living in many, many homes. Behind closed doors we’re pretty much like everyone else . . . perhaps endowed with a few more trinkets and talent, perhaps a tad more privileged - but a family none the less. And it is as a family that we shed copious tears for two family members who brought us such joy, compassion, energy and generosity. We both mourn their dreadful passing and celebrate their many, many achievements in life.

They have achieved immortality.

Wishing one and all a merry, happy everything!

IT’S ALL IN THE FAMILY

Copyright©2025 Kurt Franklin Stone.